|

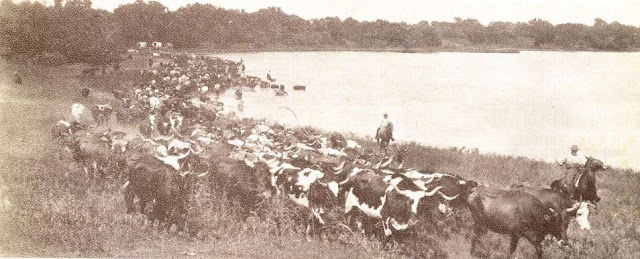

| Movie Still from the Paramount film "North of 36," which came out in 1926. It was shot in Fort Bend County, Texas, on the Blakely Ranch. Thanks to eagle-eyed reader Nancy Zimmerman for the tip. |

Though we get a lot of our information about the Old West from movies and television, what actually happened in the cattle industry in our part of Texas in the years after the Civil War was quite amazing, and often very different from what we see on the silver screen.

For example, consider the stories of J. J. Denton, a Kerr County pioneer who recalled family incidents with bands of Indians, his fondness for bear meat, and what life was like here in the very earliest days of the county. Denton's memories about cattle drives were quite surprising.

"When the men were at the front during the Civil War the cattle went wild," he remembered in a story published in J. Marvin Hunter’s Frontier Times of October, 1929. "There was nobody to brand them, and, in the absence of marks, after the war, they belonged to the first man who could clap a hot iron to them. There was a wild scramble to see who could brand the greatest number."

Without a market, though, the cattle were "almost worthless."

After the Civil War, demand for beef grew dramatically, especially in the industrialized cities of the North. Suddenly the cattle roaming unbranded here and in other parts of Texas were valuable at markets along the railheads in places like Kansas and Missouri; cattle were worth 50 cents a head in Texas, but worth $16 per head in Kansas.

The biggest problem in meeting this demand was a matter of geography. The cattle were readily available in central and south Texas, but access to railway transportation for hauling the cattle to markets was far away, in Kansas. Thus came the invention of the cattle drive, and in some ways, the invention of the Texas cowboy.

"In 1872 or 1873 the first trail herds of South Texas were gathered up,” J. J. Denton recalled. “Reports that settlers could get actual money for cattle for the mere trouble of driving them to Kansas at first found little credence among us and many refused to believe until men who were known to have started north with cattle came back and showed the gold pieces.

"From that time on the movement of cattle north increased every year. They went by the tens of thousands, making people along the route wonder where they all came from and why, after so heavy a movement, there appeared to be as many of them as there ever were still on the range."

Disbelief. That was Kerr County's initial reaction to driving cattle north.

Getting the cattle to market was imperative. Soon after the Civil War, herds were being driven to markets, though in an inefficient way. Unclaimed and unbranded cattle, mavericks, were rounded up as J. J. Denton described. Drovers were hired, often with only promises of pay after the animals were sold. Gear and supplies were purchased on credit. Thousands of cattle were driven to northern railheads in this haphazard method.

Ranching was a complicated business, separate from trailing cattle north. The rancher bought or leased pastures, stocked them with cattle, and hired hands to raise them. Ranching was focused on husbandry. The thought of sending ranch employees north on the cattle trails, to be gone for months, was impractical: those workers were needed on the ranch. Cattle drives would pull too many scarce resources away from the ranch.

To trail a herd of 3,000 cattle required at least 11 drovers, including a trail boss, plus enough food, horses, and gear to support them. Such a drive could take over two months to complete. It soon made better economic sense to hire out this task, to hire a contractor. For a flat fee, usually between $1 and $1.50 per head, the contractor would furnish drovers, trail boss, wagons, and supplies. They would sell the cattle for the rancher at the market, and forward the proceeds.

For ranchers, this made sense. It saved them money, and it allowed them to focus on raising and improving their herds. Small operations could send their cattle along with those from other ranches, gathered into larger herds, which made the drives even more efficient.

Next week, I’ll tell the story of how one partnership in the cattle trailing business came to move no fewer than 600,000 head to market and to northern pastures between 1871 and 1887. One man in the partnership was from Kerrville, and he was indispensable to the operation.

Until then, all the best.

Joe Herring Jr. is a Kerrville native who is a fan of beef, cooked over a flame, on an outdoor grill.

Though this newsletter is free, it isn't cheap. You can help by sharing it with someone, by forwarding it by email, or sharing it on Facebook. Sharing is certainly caring. (I also have two Kerr County history books available online, with free shipping!)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please remember this is a rated "family" blog. Anything worse than a "PG" rated comment will not be posted. Grandmas and their grandkids read this, so please, be considerate.